Dawn by Octavia E. Butler: A Review

I've loved Octavia Butler so deeply for so long, that it's hard now for me to imagine a world before I knew her. In my freshman year writing class, we read Parable of the Sower and it rattled me to the core. Not that prescience is the most important thing in a work of speculative fiction, but I was nevertheless astonished by how closely this world she imagined looked like the world of today. Being from Southern California, too, and recognizing the places her characters moved through, seeing a landscape I knew through an unfamiliar lens, was astonishing. I couldn't get enough.

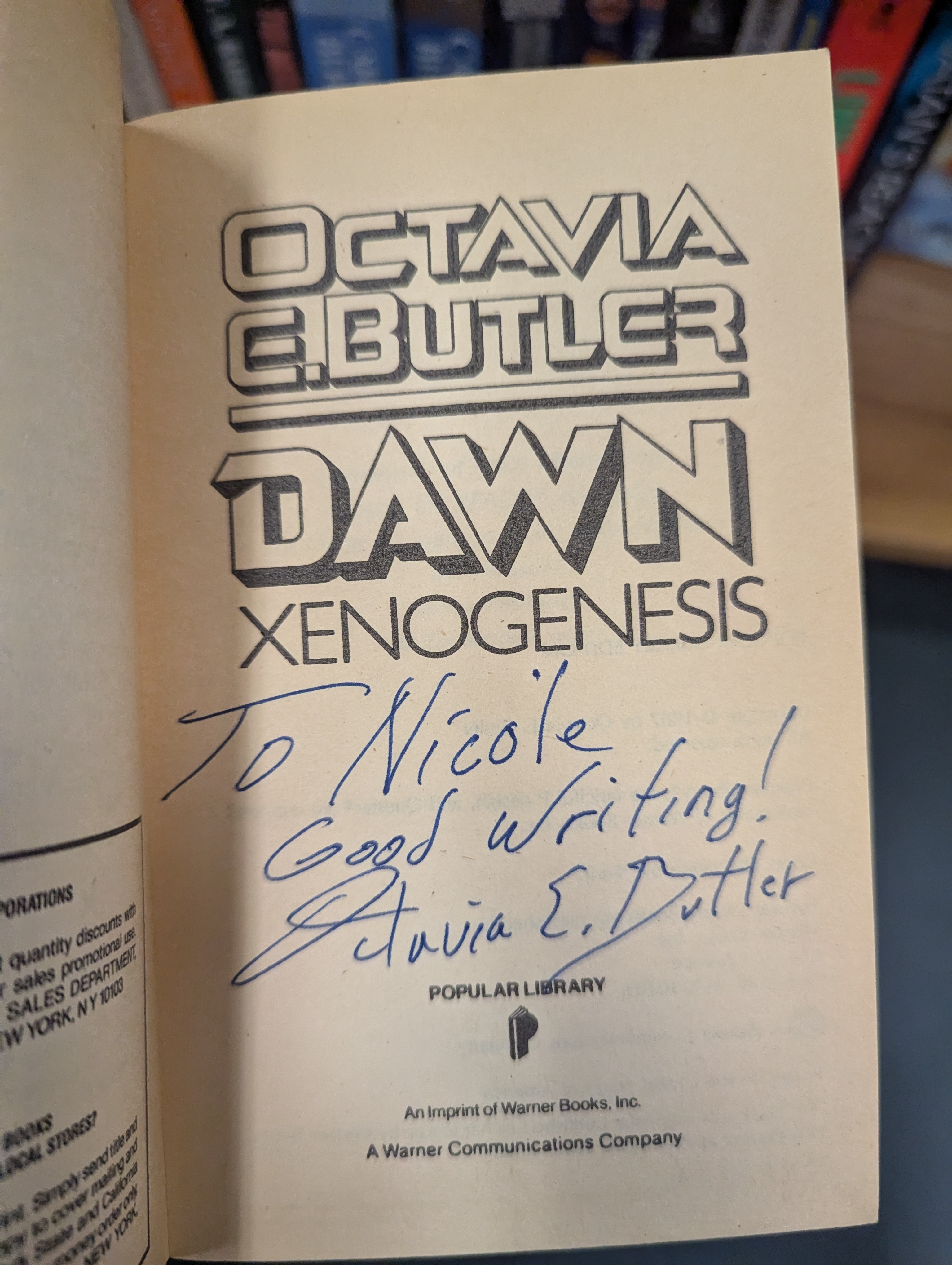

I wish I could remember when, exactly, I found Dawn, because I read almost everything else she ever wrote in such quick succession after that. All I'm missing now is Survivor (pulled from the shelves not long after publication because she hated it so much, so it may be a long time before I rectify that) and Patternmaster (easily acquired, but by now I've put it off so long, I'm almost afraid to begin—it's the last mystery of hers that remains to me, it seems like I should wait for the perfect moment).

Dawn stood out to me for its refusal to be like anything else. Its disavowal of the kinds of narrative structures I was familiar with, and its plot which, rather than building linearly, seems to meander, spiral, and explode. I also love it for how impossible it seems to adapt to pop-cultural palatability, with its tendrils and tentacles, alien sex and forced evolutions, its sensuality and rootedness in enfleshment, embodiment, ensoulment; the way it asks uncomfortable, impossible to answer questions about the meaning of difference, the meaning of humanity, what separates one human from another, one species from another, one mind from another. Ava Duvernay is reportedly adapting the story into a television series, and while I eagerly await its release, I can't help but feel that Dawn is a story too much about the things humans fear to make for successful television—though I certainly hope to be proven wrong!

The Lilith's Brood (or Xenogenesis) series is excellent all the way through, but Dawn holds a special place in my heart—the first of its kind I had ever read, and the beginning of something as deeply special, complicated, and entirely unique as the new humanity that Lilith finds herself the progenitor of.

the plot

Lilith is a young Black woman who wakes up in a strange room with no idea where she is and no memory of how she got there. Her needs are met and she's taken care of by a mysterious entity she can't quite identify, but she is not allowed to leave. Eventually, this entity reveals itself to be a member of the Oankali, an alien species that has swooped in just as humanity was about to destroy itself in a nuclear apocalypse, and rescued its few survivors. Lilith is now one of only a few human beings who remain, and she has been chosen, due to her genetic history and personality archetype, to help usher in a new era of community between the two species.

The Oankali are highly intelligent and different from humans in just about every possible way: covered in tentacles with no discernable facial features, and a mating structure completely foreign to Lilith. The Oankali have three sexes (male, female, and ooloi), and their family units include one parent of each sex, with the males and females usually being a sibling pair. Ooloi use the neuter pronoun (it/its) and use specially-designed limbs to facilitate the exchange of both genetic material and emotional intelligence between its partners, feeling what they're feeling and creating new sensations in those it touches.

The story follows Lilith as she comes to terms with her new position as an endangered species, and develops a connection with both Nikanj, an ooloi, and Joseph, a human man who was also spared from Earth's destruction. The Oankali are genetic traders, and have crossed the galaxy collecting the best adaptations that other species have to offer in an effort to be constantly growing and adapting. Their spaceship itself is a distant ancestor, a living being with whom the Oankali traded genetics to help facilitate their endless evolution. Lilith soon learns that the Oankali wish to exchange genetics with humans next, and hope to evolve yet again to integrate the greatest genetic gift humans have to offer: the propensity for cancer, which, when edited by ooloi geneticists, allows the species almost limitless potential for adaptability and change. Lilith is tasked with the job of convincing humans to accept this trade and take up relations with Oankali families, ushering in a new species of human-Oankali hybrids. Both human and Oankali as they currently are will cease to exist, they say, and this hybridization will be their future.

The plot itself is relatively spare, but the story is rich with thematic implications and difficult conversations that Butler refuses to shy away from. The human taboos against incest, prejudices against intersex bodies, anxieties about sexuality, hazy boundaries around consent and coercion, racial formation, the ways that identity and history undeniably alter what it means to be human—these topics make for an uneasy reading experience. Readers may find themselves reaching for some simple answer, some easy villain to point to. There are humans who accept the Oankali and those who refuse their offer, and some from each group resort to violence. The boundaries of identity become porous, as the elements which previously defined human experiences—class, gender, race, sexuality, body type—become radically reorganized and redefined. It is significant that Lilith, the mother of this new "brood" (as the later rerelease of the series terms it) is a Black woman. The other humans, let loose in an enclosed area of the ship, target her with racial and sexual violence; but she also finds connection with others through these same loci, forging a close bond with a Chinese-American man named Joseph, first as friends, then as lovers.